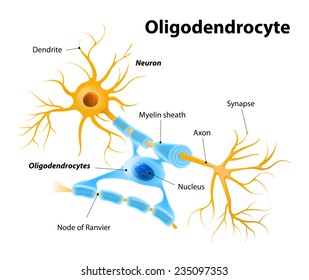

Like most of you, at least some portion of my day is spent scrolling through the various emails that I receive from organizations that I follow, family and friends passing along interesting topics or articles, and digital copies of magazines and journals. It takes some time, but often means gathering nuggets of information that shed light on the future of neural research and treatment of neurological conditions. BTW, this is why I chose neuropsychology as a career. It is a dynamic and changing field with new research every day that proves that we don’t really understand the brain and have a lot to learn. I never feel like I have reached the point where there is nothing left. Today’s post is a summary of an article that was passed along to me by my favorite person on the autism spectrum; my dad. I have included a link to the article at the bottom for those of you who enjoy research mumbo jumbo. For those of you who like to receive your data in a form that requires burning fewer brain calories, I will make an attempt to put my interpretation of the findings into a summarized form. First a little background; your brain communicates through a combination of electrical signals and chemical signals. The electrical portion of the communication process travels from axon to axon to get from one place to another. When axons are immature and not yet in their adult form, they may lack the protective layer that surrounds the axon, which is called myelin. This is a fatty layer that forms in order to protect the communication, kind of like a copper wire that has a plastic sheath around it so that it does not discharge its electrical energy along the way.

The process of building myelin around axons in your brain happens in a specific sequence as your brain “works on” development in areas over time. Full maturation is possible in some brain areas when you are very young, but other parts won’t reach full maturity until you are in your early to mid 20’s. Either way, the process of developing myelin in needed to support brain communication and neural function. If you have too much myelin, it can cause difficulties in transmitting signals. If you have too little myelin in a brain region, those cells are often vulnerable to damage and dysfunction.

When research is completed in the neurosciences, it often starts with animal studies. Working with human brains is tricky, so research with humans is often the last part, after animal models suggest there might be some meaningful evidence. In the case of this article, there have been mouse studies that suggest when there is alteration to a specific portion of the gene sequence that is disrupted in some people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), that there is associated difficulty with myelination. There are a set of “helper” cells in your brain that facilitate the process of myelination to occur. They are called oligodendrocytes.

The wonderful part about your brain is that the “baby” cells in your brain have some flexibility in what their job ends up being when they are mature. But, this is only helpful if they are in the right place, at the right time, and with the right level of maturity. The article reviewed suggests that in those with ASD, there are too few oligodendrocytes and/or that the ones that are there are immature. This means that the support systems needed for appropriate levels of myelination is compromised when the genetic variation found is present. The positive news is that the ones that are present appear to be functional. So, what does this mean for now? The unfortunate part about research is that it offers preliminary guidance, but then lots of other super smart people have to add to it with their own more specific ways to use that knowledge in a helpful way. This means time.

But, the silver lining for this study is that we can take some guidance offered by researchers in other fields and apply that knowledge today. Nutrition studies have found that long-chain fatty acids, iron, choline, sphingomyelin and folic acid are significantly associated with early myelination trajectories. This means that we could offer immediate nutritional support to add these components.

I personally was unable to nurse my own children, but there is a huge amount of research that supports that myelin production is better in children who receive breastmilk for longer periods of time in infancy. So, nurse if you can and want to, or maybe consider using a milk bank or donor system if you can access one. For those of you with older children, adding nutritional elements like a high quality omega-3 fatty acid supplement (ask a nutritionist or doctor, there is a lot of sub-beneficial stuff out there) can help with those long chain fatty acids. To increase iron, consider adding high-iron foods such as beef, pork, poultry, and seafood (for meat eaters), tofu, dried beans and peas, dried fruits, leafy dark green vegetables, and iron-fortified breakfast cereals, breads, and pastas (for omnivores and those with more vegetarian preferences). To help make sure kids get enough iron through strong absorption, limit the amount of milk they drink to about 16–24 fluid ounces a day (too much can interfere with iron metabolism), serve iron-fortified infant cereal until kids are 18–24 months old, serve iron-rich foods (listed above) alongside foods containing vitamin C (such as tomatoes, broccoli, oranges, and strawberries), since Vitamin C improves iron absorption. Avoid serving caffeinated beverages at mealtimes, as they contain tannins that reduce the way the body absorbs iron.

You can also consider adding food choices rich in choline like meat, poultry, fish, dairy products, and eggs. Beef liver is particularly high in choline and iron, but good luck getting your child to eat it! Sphingomyelin is found in higher quantities in dairy products, eggs, and soybeans. Foods high in folic acid are very common in some form in most kid diets including choices like vegetables (especially dark green leafy vegetables), fruits and fruit juices, nuts, beans, peas, seafood, eggs, dairy products, meat, poultry, and grains. Some may not love all of these but they are bound to approve of some. Spinach, liver (look, it showed up again!), asparagus, and brussels sprouts are among the foods with the highest folate levels. These may also be low on the food love spectrum for kids, so maybe adding spinach to that smoothie is a possibility.

We are definitely in iffy territory for most kids with some of these food options, but if you are creative and foster adventurous eating habits, you should be able to trickle in a lot of these options for toddlers and older children. Feed your brain people!

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-019-0578-x#Abs1